Sidney Dillon Ripley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sidney Dillon Ripley II (September 20, 1913 – March 12, 2001) was an American

A friend of the Ripleys,

A friend of the Ripleys,

Ripley had intended to produce a definitive guide to the birds of

Ripley had intended to produce a definitive guide to the birds of

Biography

from the

Biography and obituary

in ''Smithsonian'' magazine

in ''The New York Times''

Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ripley, Sidney Dillon 1913 births 2001 deaths Military personnel from New York City Writers from New York City Yale University alumni Columbia University alumni Harvard University alumni 20th-century American Episcopalians American ornithologists Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution People of the Office of Strategic Services Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering 20th-century American zoologists Scientists from New York City Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients American expatriates in India Members of the American Philosophical Society

ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

and wildlife conservation

Wildlife conservation refers to the practice of protecting wild species and their habitats in order to maintain healthy wildlife species or populations and to restore, protect or enhance natural ecosystems. Major threats to wildlife include habita ...

ist. He served as secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

for 20 years, from 1964 to 1984, leading the institution through its period of greatest growth and expansion. For his leadership at the Smithsonian, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

by Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

in 1985.

Biography

Early life

Ripley was born inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, after a brother, Louis, was born in 1906 in Litchfield, Connecticut. His mother was Constance Baillie Rose of Scottish descent while his father was Louis Arthur Dillon Ripley, a wealthy real estate agent who drove around in an 1898 Renault Voiturette

The Renault Voiturette (Renault Little Car) was Renault's first ever produced automobile, and was manufactured between 1898 and 1903. The name was used for five models.

The first Voiturettes mounted De Dion-Bouton engines. Continental tires were u ...

. Both his paternal grandparents, Julia and Josiah Dwight Ripley, died before he was born but he connected to them was through Cora Dillon Wyckoff. Great Aunt Cora and her husband, Dr. Peter Wyckoff, often hosted young Ripley at their Park Avenue

Park Avenue is a wide New York City boulevard which carries north and southbound traffic in the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. For most of the road's length in Manhattan, it runs parallel to Madison Avenue to the west and Lexington Avenu ...

apartment. Cora's and Julia's father (his great-grandfather) and partial namesake was Sidney Dillon, twice President of the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

. and his uncle was Sidney Dillon Ripley I. Both Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

tycoons.

Ripley's early education was at the Montessori Kindergarten School on Madison Avenue. As a young boy, he traveled widely including to British Columbia where his mother's relatives lived. In April 1918, his mother, who had separated from his father, moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts. In 1919 the family moved again to Boston, where he studied in a school called Rivers. At the age of ten, he traveled again with his mother across Europe. In 1924 Ripley went to a boarding school called Fay in Southborough, Massachusetts.

In 1926 he followed in Louis' footsteps, attending St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third largest city in New Hampshire behind Manchester and Nashua.

The village of ...

. In 1936, he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. While at Yale he briefly considered a more traditional career path after a conversation with his brother. “Louis told me we ought to have a lawyer in the family,” he has said, “but I really hated the idea, and in the summer of 1936, after graduating from college, I resolved to abandon all thoughts of a prosperous and worthy future and devote myself to birds, the subject I was overpoweringly interested in.”

Travel and education

A friend of the Ripleys,

A friend of the Ripleys, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, whose father founded the Young Men's Christian Association, and Celestine Mott were planning a visit to India to set up a YMCA hostel in India. This led to a visit to India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

at age 13, along with his sister. They stayed at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay and then went to Kashmir and included a walking tour into Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

and western Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

. In Kashmir, they flew falcons with Colonel Biddulph. They also visited Calcutta and Nagpur. One of Ripley's brothers shot a tiger at a shoot hosted by a Maharaja. This led to his lifelong interest in the birds of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. He returned to St Paul's to complete his studies. It was suggested to him that Yale would be the best for him. Ripley received a training in making specimens from Frank Chapman and even had tea once as a sophomore Erwin Stresemann. He decided that birds were more interesting than law and after graduating from Yale in 1936 he was advised by Ernst Mayr that "the most important thing you can do is get a sound and broad biological training." He then enrolled at Columbia University. and he began studying zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. As a part of his study, Ripley participated in the Denison-Crockett Expedition to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

in 1937-1938 and the Vanderbilt Expedition to Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

in 1939. He later obtained a PhD in Zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1943.

War service and academic work

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he served under William J. Donovan

William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan (January 1, 1883 – February 8, 1959) was an American soldier, lawyer, intelligence officer and diplomat, best known for serving as the head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to the Bur ...

("Coordinator of Information") in the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

, the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. In the early days Ripley acted as liaison with the British Security Coordination led by Sir William Stephenson at the Rockefeller Center. He later was in charge of American intelligence services in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

. Others who joined the OSS early included Ripley's Yale friends Sherman Kent and Wilmarth S. Lewis. Ripley held a high regard for his OSS colleagues and considered it unfair on the part of some to decry those who were socially inclined leading to some calling the organization as "Oh So Social". Ripley trained many Indonesian spies, all of whom were killed during the war. He was posted briefly to Australia with the identity of a lieutenant colonel in case he was captured. He was to go through England, Egypt, China and then on to India and Ceylon. He then worked with Detachment 404 in Bangkok, working to recover Allied airmen who had been captured in the region with the help of friendly Thais who worked to keep them under cover from the Japanese forces. After this period he moved to Sri Lanka and never got to Australia as originally planned. He worked with and "cultivated" Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

throughout this period. The two often met at dinners and parties both in New Delhi and at Trincomalee. On one occasion, Ripley noticed a green woodpecker and went off to shoot it while dressed only in a towel. The specimen label reads "Shot at cocktail party... towel fell off." It was in Kandy, Sri Lanka that he met his future wife Mary Livingston

Mary Livingston (c. 1541–1582) was a Scottish noblewoman and childhood companion of Mary, Queen of Scots, one of the famous "Four Marys".

Life

Mary Livingston was born around 1541, the daughter of Alexander Livingston, 5th Lord Livingston (c. ...

and her roommate Julia Child

Julia Carolyn Child (née McWilliams; August 15, 1912 – August 13, 2004) was an American cooking teacher, author, and television personality. She is recognized for bringing French cuisine to the American public with her debut cookbook, '' ...

(then Julia McWilliams) both working with the OSS. The anthropologist Gregory Bateson was also here and he would introduce Julia to Paul Child, her future husband. An article in the August 26, 1950 ''New Yorker

New Yorker or ''variant'' primarily refers to:

* A resident of the State of New York

** Demographics of New York (state)

* A resident of New York City

** List of people from New York City

* ''The New Yorker'', a magazine founded in 1925

* ''The New ...

'' said that Ripley reversed the usual pattern, where spies posed as ornithologists in order to gain access to sensitive areas, and instead used his position as an intelligence officer to go birding in restricted areas. The government of Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

awarded him the Order of the White Elephant, a national award for his support of the Thai underground during the war. In 1947, Ripley entered Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mai ...

pretending to be a close confidante of Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and the Nepal government, eager to maintain diplomatic ties with its newly independent neighbour, allowed him and Edward Migdalski to collect bird specimens. Nehru came to hear of this from an article in ''The New Yorker'' and was furious, leading to a difficult time for his collaborator and coauthor, Salim Ali

Sálim Moizuddin Abdul Ali (12 November 1896 – 20 June 1987) was an Indian ornithologist and naturalist. Sometimes referred to as the "''Birdman of India''", Salim Ali was the first Indian to conduct systematic bird surveys across Indi ...

. Salim Ali came to hear of Nehru's displeasure through Horace Alexander and the matter was forgiven after some effort. The OSS past however led to a growing suspicion that American scientists working in India were CIA agents. David Challinor, a former Smithsonian administrator, noted that there were many CIA agents in India, with some posing as scientists. He noted that the Smithsonian sent a scholar to India for anthropological research who unknown to them was interviewing Tibetan refugees

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken dial ...

from Chinese-occupied Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

but went on to say that there was no evidence that Ripley worked for the CIA after he left the OSS in 1945.

He joined the American Ornithologists' Union

The American Ornithological Society (AOS) is an ornithological organization based in the United States. The society was formed in October 2016 by the merger of the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) and the Cooper Ornithological Society. Its m ...

in 1938, became an Elective Member in 1942, and a fellow in 1951. After the war he taught at Yale and was a Fulbright fellow

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

in 1950 and a Guggenheim fellow

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

in 1954. At Yale, one of the key scientific influences on Ripley was the ecologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson, who had led the Yale expedition to India in 1932. Ripley became a full professor and director of the Peabody Museum of Natural History

The Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University is among the oldest, largest, and most prolific university natural history museums in the world. It was founded by the philanthropist George Peabody in 1866 at the behest of his nephew Othn ...

. Ripley served for many years on the board of the World Wildlife Fund

The World Wide Fund for Nature Inc. (WWF) is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named the Wo ...

in the U.S., and was the third president of the International Council for Bird Preservation

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

(ICBP, now BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding ...

).

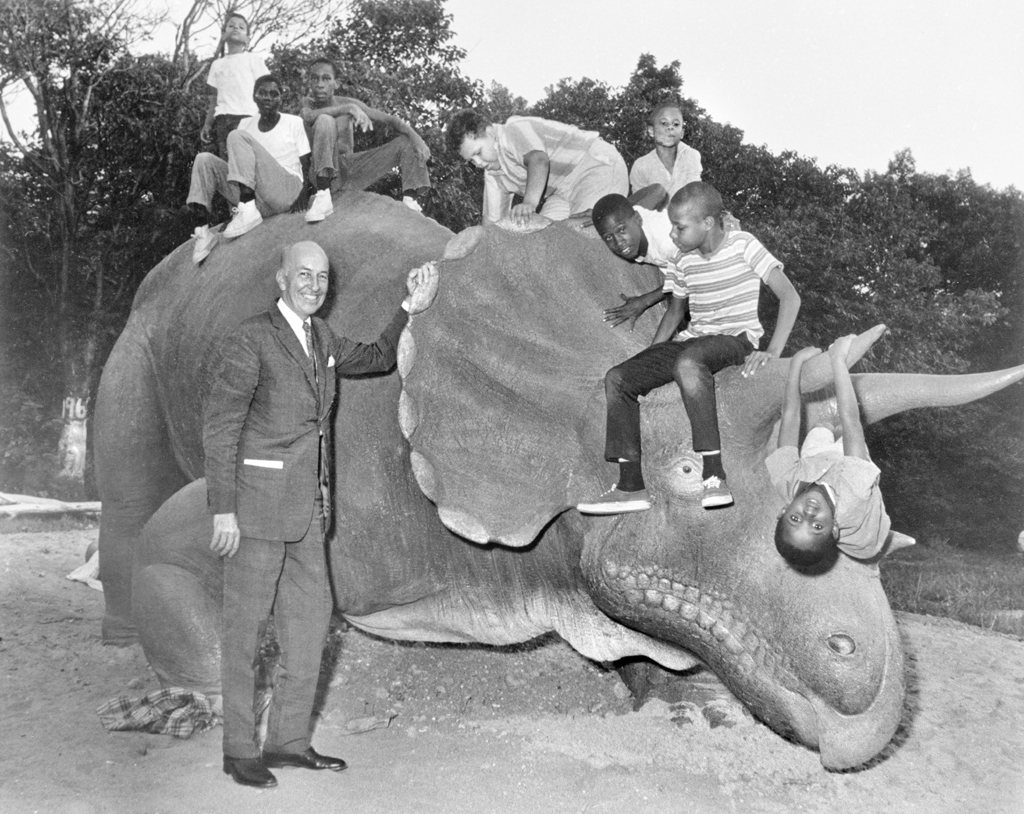

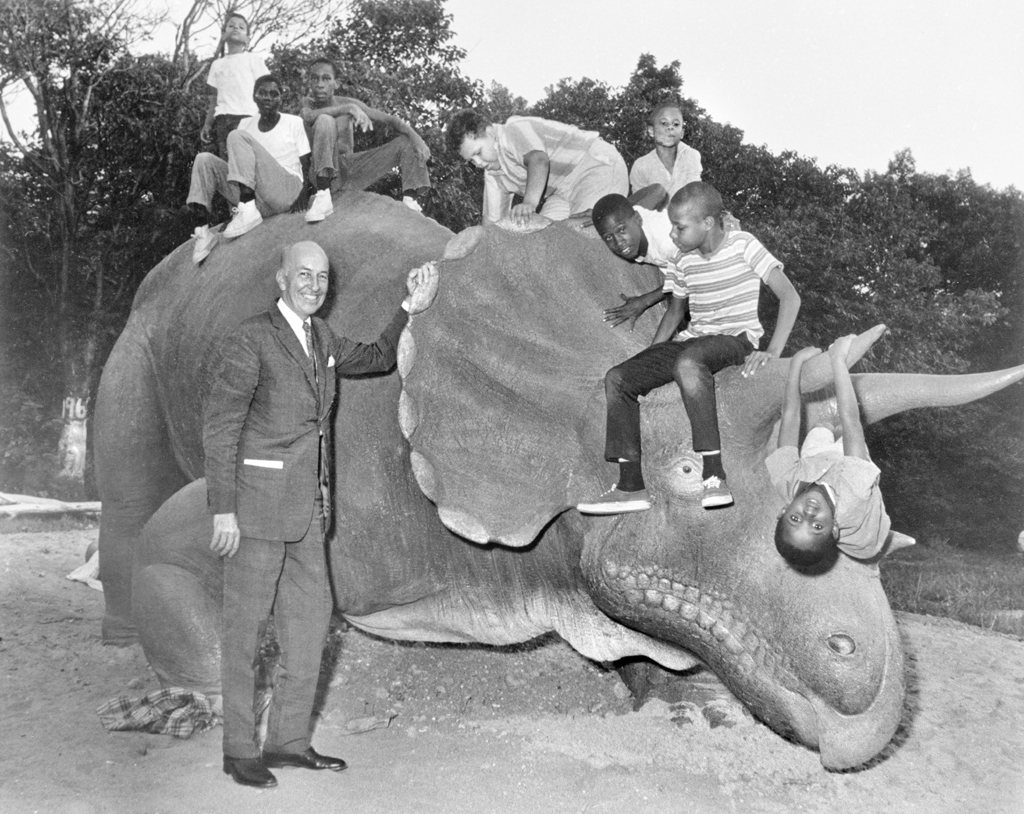

Smithsonian Institution

He served as Secretary of theSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

from 1964 to 1984. He set out to reinvigorate and expand the Smithsonian, building new museums, including the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, now the Anacostia Community Museum

The Anacostia Community Museum (known colloquially as the ACM) is a community museum in the Anacostia neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. It is one of twenty museums under the umbrella of the Smithsonian Institution and was th ...

, Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum is a design museum housed within the Andrew Carnegie Mansion in Manhattan, New York City, along the Upper East Side's Museum Mile. It is one of 19 museums that fall under the wing of the Smithsonian Inst ...

, Hirshhorn Museum

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is an art museum beside the National Mall, in Washington, D.C., the United States. The museum was initially endowed during the 1960s with the permanent art collection of Joseph H. Hirshhorn. It was des ...

and Sculpture Garden

A sculpture garden or sculpture park is an outdoor garden or park which includes the presentation of sculpture, usually several permanently sited works in durable materials in landscaped surroundings.

A sculpture garden may be private, owned by a ...

, Renwick Gallery

The Renwick Gallery is a branch of the Smithsonian American Art Museum located in Washington, D.C. that displays American craft and decorative arts from the 19th to 21st century. The gallery is housed in a National Historic Landmark building that ...

, National Air and Space Museum

The National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, also called the Air and Space Museum, is a museum in Washington, D.C., in the United States.

Established in 1946 as the National Air Museum, it opened its main building on the Nat ...

, National Museum of African Art

The National Museum of African Art is the Smithsonian Institution's African art museum, located on the National Mall of the United States capital. Its collections include 9,000 works of traditional and contemporary African art from both Sub-S ...

, Enid A. Haupt Garden, the underground quadrangle complex known as the S. Dillon Ripley Center, and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery

The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery is an art museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., focusing on Asian art. The Sackler Gallery and the Freer Gallery of Art together form the National Museum of Asian Art in the United States. Th ...

.

In 1967, he helped found the Smithsonian Folklife Festival

The Smithsonian Folklife Festival, launched in 1967, is an international exhibition of living cultural heritage presented annually in the summer in Washington, D.C. in the United States. It is held on the National Mall for two weeks around the F ...

, and in 1970, he helped found '' Smithsonian'' magazine. He believed that 75% to 80% of then-living animal species would become extinct in the next 25 years. R Bailey (2000) ''Earth day then and now'', Reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

32(1), 18-28

In 1985 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

, the highest civilian award of the United States. He was awarded honorary degrees from 15 colleges and universities, including Brown

Brown is a color. It can be considered a composite color, but it is mainly a darker shade of orange. In the CMYK color model used in printing or painting, brown is usually made by combining the colors orange and black. In the RGB color model used ...

, Yale, Johns Hopkins

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in Baltimore, Maryland where he remained for most ...

, Harvard, and Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. He was a member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

, the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

.

Ripley successfully defended the National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. In 2021, with 7 ...

against a lawsuit that objected to the ''Dynamics of Evolution'' exhibit.

Legacy

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

, but became too ill to play an active part in its realisation. However, the eventual authors, his assistant, Pamela C. Rasmussen, and artist John C. Anderton, named the final two-volume guide as '' Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide'' in his honor.

The Smithsonian's underground complex on the National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institut ...

, the S. Dillon Ripley Center, is named in his honor. A garden between the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden is an art museum beside the National Mall, in Washington, D.C., the United States. The museum was initially endowed during the 1960s with the permanent art collection of Joseph H. Hirshhorn. It was des ...

and the Arts and Industries Building

The Arts and Industries Building is the second oldest (after The Castle) of the Smithsonian museums on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Initially named the National Museum, it was built to provide the Smithsonian with its first proper facil ...

was dedicated in 1988 to his wife, Mary Livingston Ripley

Mary Moncrieffe Livingston Ripley (May 11, 1914 – April 15, 1996) was a U.S. horticulturist, entomologist, photographer, and scientific collector.

Early life

Mary Livingston was born in New York City in 1914. She was the daughter of Gerald M ...

.

The first-ever full-length biography of Ripley, ''The Lives of Dillon Ripley: Natural Scientist, Wartime Spy, and Pioneering Leader of the Smithsonian Institution'' by Roger D. Stone, was published in 2017.

The Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy, a non-profit zoo dedicated to breeding endangered waterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

, is located on 150-acres of the Ripley estate in Litchfield, Connecticut. The zoo's history began in the 1920s when Ripley began keeping and breeding waterfowl as a teenager, and he is credited with the first captive breedings of Red-breasted goose

The red-breasted goose (''Branta ruficollis'') is a brightly marked species of goose in the genus ''Branta'' from Eurasia. It is currently classified as vulnerable by the IUCN.

Taxonomy and etymology

The red-breasted goose is sometimes placed ...

, Nene, Emperor goose

The emperor goose (''Anser canagicus''), also known as the beach goose or the painted goose, is a waterfowl species in the family Anatidae, which contains the ducks, geese, and swans. It is blue-gray in color as an adult and grows to in length. ...

, and Laysan Teal as well as the first US captive breedings of New Zealand scaup, Greenland Mallard

The mallard () or wild duck (''Anas platyrhynchos'') is a dabbling duck that breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, Arge ...

(''A. p. conboschas''), and Philippine duck

The Philippine duck (''Anas luzonica'') is a large dabbling duck of the genus ''Anas''. Its native name is ''papan''. It is endemic to the Philippines.

It eats shrimp, fish, insects, and vegetation, and it frequents all types of wetlands.

Tax ...

. In 1985, Dillon and his wife, Mary Livingston Ripley, donated the chunk of their estate that is today the zoo to the non-profit organization that continues to operate it. Today the zoo houses over 60 species of birds, totaling over 400 individual animals. Ripley's three daughters continue to serve on the zoo's board of directors.

Selected writings

*''The Land and Wildlife of Tropical Asia'' (1964; Series: LIFE Nature Library) *''Rails of the World: A Monograph of the Family Rallidae'' (1977) *''The paradox of the human condition : a scientific and philosophic exposition of the environmental and ecological problems that face humanity'' (1975) *''Birds of Bhutan'', with Salim Ali and Biswamoy Biswas *''Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan

The ''Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan'' is the ''Masterpiece, magnum opus'' of Indian ornithologist Salim Ali, written along with S. Dillon Ripley. Appended to the title is the phrase "''together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Sikkim ...

'', with Salim Ali (10 volumes)

*''The Sacred Grove: Essays on Museums'' (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1969)

Notes

References

*Stone, Roger D. (2017) The Lives of Dillon Ripley. ForeEdge. *External links

Biography

from the

Smithsonian Institution Archives

Smithsonian Libraries and Archives is an institutional archives and library system comprising 21 branch libraries serving the various Smithsonian Institution museums and research centers. The Libraries and Archives serve Smithsonian Institution ...

Biography and obituary

in ''Smithsonian'' magazine

in ''The New York Times''

Livingston Ripley Waterfowl Conservancy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ripley, Sidney Dillon 1913 births 2001 deaths Military personnel from New York City Writers from New York City Yale University alumni Columbia University alumni Harvard University alumni 20th-century American Episcopalians American ornithologists Secretaries of the Smithsonian Institution People of the Office of Strategic Services Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering 20th-century American zoologists Scientists from New York City Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients American expatriates in India Members of the American Philosophical Society